Every Object Tells a Story

On November 3, 1941, the U.S. War Department Chemical Warfare Service established an installation on a 21-square-mile tract about 5 miles north of its namesake city. At the time, the city we know as White Hall was an unnamed, unincorporated village that had built up around a local landmark called Crenshaw Spring.

White Hall owes much of its growth and success to the Pine Bluff Arsenal, adjacent to White Hall’s northeast city limits. The histories of the arsenal and the city are permanently entwined. A significant portion of the museum’s collection documents this historic partnership from a unique point of view.

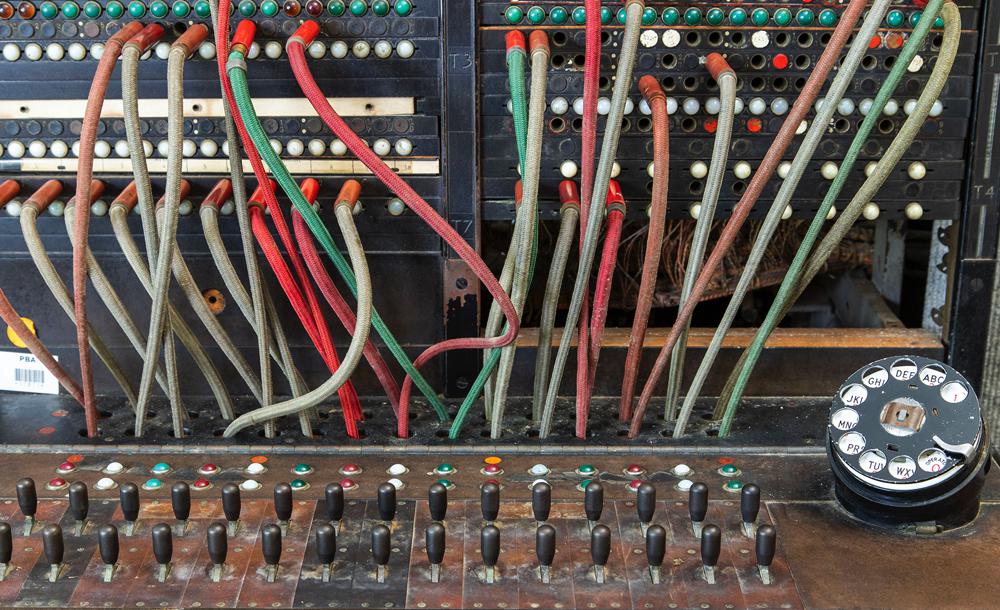

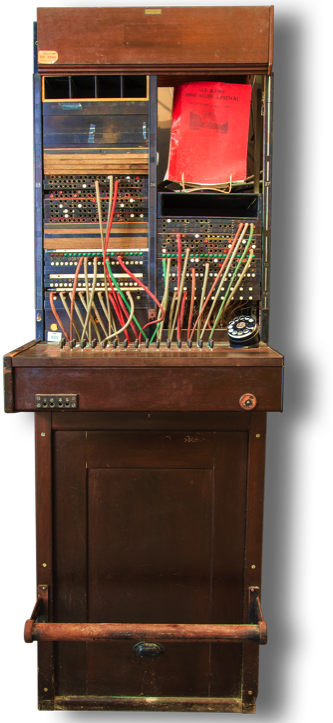

As a busy military post, the arsenal was abuzz with incoming, outgoing and interdepartmental phone calls. With computerized call switching several decades away, calls were actually connected by operators perched on stools as they pulled and inserted wired plugs on a switchboard. Pictured is one of several switchboard modules that were ganged together to handle the large call volume at the arsenal.

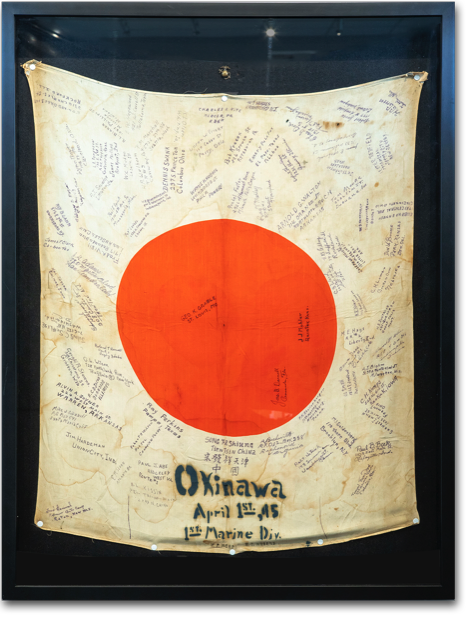

This framed Japanese flag, or Hinomaru, is on loan to the museum from Paul Wilson. It was brought home by his grandfather, W.P. Murphy as a souvenir of his service in Okinawa, Japan, during World War II.

As part of the III Amphibious Corps, the First Marine Division was shipped from the island of Pelelieu to Okinawa to fight alongside U.S marines in the 6th Marine Division against Japan’s 32nd Army. This flag was autographed by members of the batallion to commemorate their April 1, 1945, landing.

No actual valuation of the flag exists, but it is known that a successful Hollywood film producer saw the flag when visiting the museum, and offered to buy the flag for $50,000. The impressive offer was declined.

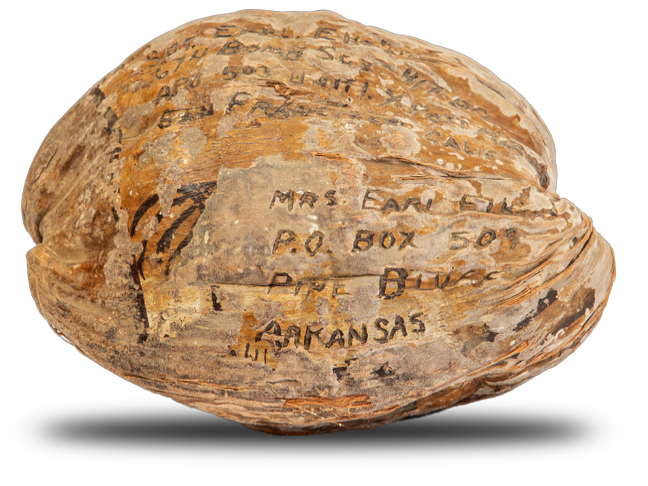

During World War II, U.S. combat troops were prohibited from disclosing their location to friends and family.

However, Sgt. Earl Elkins devised a clever means of informing his wife, Dorothy, of his approximate location and that he was doing fine.

Using a sharp point, he engraved the shell of a coconut with his wife’s name and address, then mailed it to her through the Army Post Office.

When she received the unique “postcard,” Dorothy couldn’t know exactly where her husband was, but she knew he was in a place where coconuts grow!

Not everything in the museum’s collection is about the serious business of military warfare and preparedness!

This gramophone, manufactured by the Victor Talking Machine Company of Camden, NJ, circa 1900 represents the important transition from fragile and bulky wax cylinders to the more convenient wax disc format, or “records.” The discs were fragile, but easier to store.

Sound recorded for gramophones used the "acoustic" method, which was basically the reverse of the players’ technology. A large, brass horn collected the sound, focused it on an apparatus containing a needle which etched a wax “master” as it vibrated. A metal master was cast from the wax original, and was used to embed grooves in wax copies.

Eventually, the wax discs gave way to discs coated with shellac, which was more durable.

When the gramophone was invented, electricity was still not available to everyone, so the turntable was powered by a mechanism similar to a clock movement that was “wound up” using a hand-crank.

The Pine Bluff Arsenal was originally commissioned to manufacture and store incendiary devices, such as grenades and bombs. Soon, the arsenal’s mission was expanded to include pyrotechnic, riot control and chemical munitions.

This is an early example of a rifter that was used to fill the canisters of smoke grenades, such as the well-known M-18, used by the military in ground combat.

Precise quantities of the smoke material had to be loaded into the canisters. Too little, and the grenade wouldn’t work. Too much, and the grenade became too dangerous to handle. This device ensured that the correct amount was loaded.

The treasure of objects at the White Hall Museum is an eclectic assortment of artifacts and memorabilia, with an accent on military and domestic history. While every object is unique, they all share in common the ability to tell a story and offer an insight into the rich tapestry that illustrates White Hall’s life in both the recent and bygone past.

The nation’s very first “Touch Tone” telephones were made available to the public in the same year that White Hall was officially incorporated, on October 29, 1964.

Students at Moody Elementary School were given a Social Studies assignment to craft scale models of the traditional dwellings of Arkansas’ indigenous peoples. These fascinating replicas were the result.